A new study suggests post-treatment active infection and autoimmunity are not necessarily opposing viewpoints about PTLDS, opening the door to more effective treatment options.

A recent study at the University of Utah has made news establishing a link between infection, immune response, and ongoing arthritic symptoms in Lyme disease. This study integrates different views about the etiology of what is often called “Chronic Lyme,” “Post Treatment Lyme Disease” (PTLD) or “Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome” (PTLDS).

There are two dominant theories about what causes ongoing health problems (including joint pain, fatigue, muscle aches, cognitive problems, insomnia, and mood disorders) in patients previously treated for Lyme disease. One view is that chronic symptoms are caused by a persisting infection. A second view is that PTLDS symptoms are caused by an autoimmune response, triggered by a previous infection. These views are often considered opposing because treatment for an autoimmune disorder could be vastly different than treatment of a chronic, active infection.

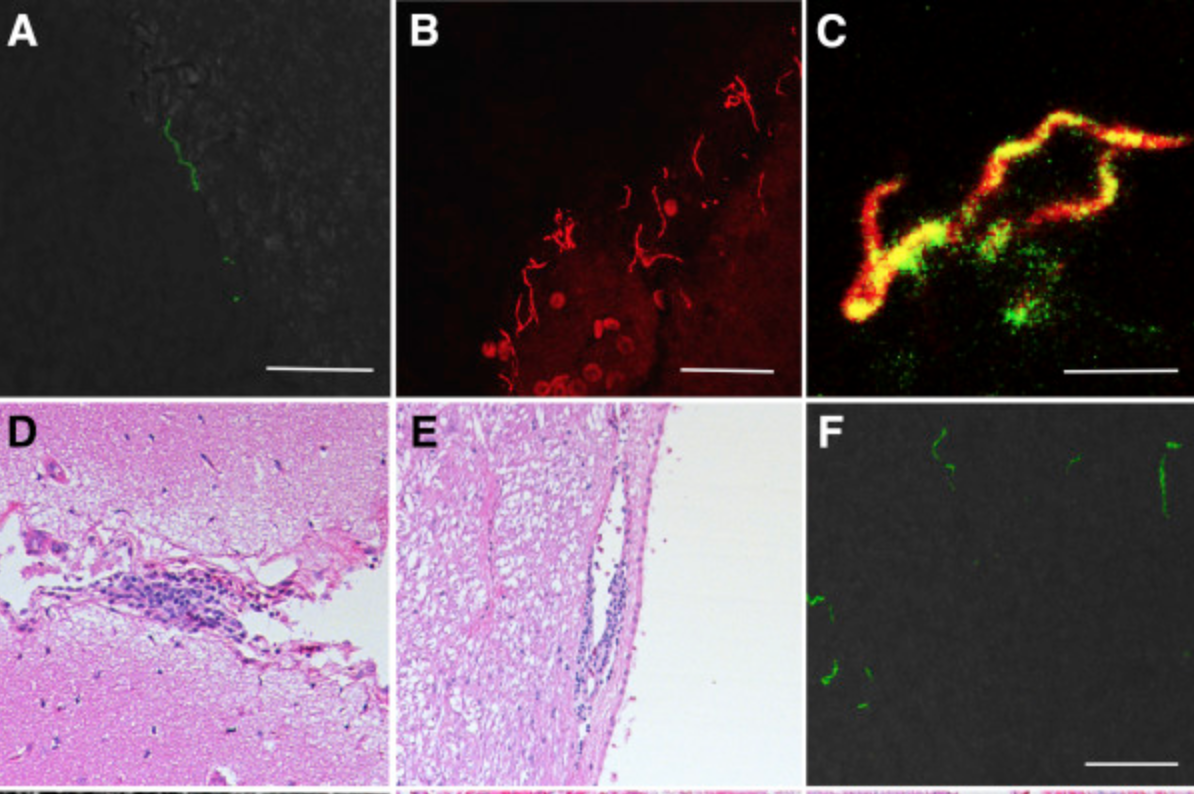

To better understand this study it is helpful to understand that ‘T cells’ are necessary for most adaptive immune responses. T cells help other cells activate to destroy microbes or target and kill infected cells. Different ‘signals’ activate T cells and determine the type of immune response elicited. The study showed molecules on the surface of Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, interact with T cells resulting in an inflammatory response. Using an experimental model of overactive inflammation the researchers considered that “residual, persisting bacteria” can interact with these and other “bystander” T cells, producing a “cascading cycle of inflammation that could lead to infection-induced autoimmunity.”

This is not an unfamiliar concept. At the 2017 Lyme Disease Association conference in Philadelphia, Dr. Nicole Baumgarth, DVM, Phd, explained, “Lyme disease is an inflammatory disease triggered by an activation of the immune response in reaction to Borrelia burgdorferi“. According to Johns Hopkins researcher, Dr. Ying Zhang, possible causes of PTLDS include: host response, autoimmune disorders, residual damage to tissues, persisting (post treatment) infection, and co-infections. He noted, “These are not mutually exclusive”.

We often think of “Lyme disease” as being the bacterial infection, however, similar to the common cold (where it is not the virus itself but instead inflammatory mediators triggered by the presence of the virus that cause symptoms like headaches and congestion), it is inflammation that causes Lyme disease symptoms, not the infection itself. Because our bodies respond in unique ways to infectious agents some people can have a high bacterial load without disease symptoms, while others respond differently and become quite ill. By separating the “pathogen” (Borrelia burgdorferi) and the “disease” (symptoms due to inflammation) we can better understand why reducing the bacterial load sometimes does not affect symptoms, and how low levels of residual bacteria can trigger an ongoing immune response potentially leading to a type of PTLD that is caused by an out-of-control immune system.

While this study focused on arthritic symptoms being the result of an infection-induced immune response, understanding the broader effects of inflammation could explain a wider range of Chronic Lyme/PTLDS symptoms, including vision problems, cognitive difficulties, and mood disorders. According to Dr. Robert Bransfield, “You do not need an infection in the brain to cause symptoms – inflammation can do this.”

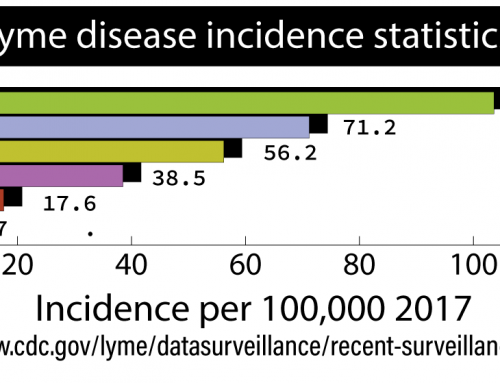

Dr. Christopher D. Paddock of the CDC has noted that two-thirds of all identified tick-borne pathogens have only been identified in the past 30 years. We are just beginning to understand these pathogens, and how to effectively treat the diseases they cause. This recent study suggests post-treatment active infection and autoimmunity are not necessarily opposing viewpoints about PTLDS. For patients used to identifying with one camp or the other this can seem confusing, but when the sole treatment focus is on eradicating infection the immune response may not be adequately addressed, and when managing inflammation is the main treatment goal persisting bacterial infections may lead to autoimmune disorders. A better understanding of this relationship between persistent infection and immune dysregulation will lead to more effective treatments for complex Lyme disease.