In September, 2018 the Vermont Department of Health (VDH) posted a webinar to help health care providers learn about the diagnosis and treatment of tick-borne diseases in Vermont. In our mission to provide Vermonters with accurate, equitable information about Lyme and TBDs, VTLyme.org highlights information in the VDH webinar and offers additional insight and information, especially regarding the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease.

The objectives of the VDH webinar are listed as: “1. Review the epidemiology of tickborne diseases in Vermont, 2. Define the symptoms of Lyme diseases, anaplasmosis, babesiosis and Borrelia miyamotoi infections, 3. Identify tests used to diagnose tickborne diseases common in Vermont, 4. Describe the appropriate use of antibiotics in treating Lyme diseases, anaplasmosis, babesiosis and Borrelia miyamotoi infections.” A health care provider can earn Continuing Education credits for viewing the webinar by completing a short test and submitting a form to AHEC. The webinar is available with audio on YouTube and as a separate slideshow.

The webinar was uploaded on September 20, 2018. As of September 3, 2019 it had 160 views. There are no comments on the webinar because comments are disabled. There is no way to know what percentage of the 160 views are by health care providers in Vermont, but AHEC confirmed that, as of September 5, 2019, six health care providers earned CE credits by submitting the short test. Four of these were CME, and two were nursing credits.

COURSE OBJECTIVE #1: Epidemiology

The review of the epidemiology of tickborne diseases (TBDs) by Bradley Tompkins (formerly of the VDH) offers information about the increasing incidence of TBDs in Vermont, disease trends, locations where Vermonters are most at risk for being infected, and how the life cycle of Ixodes scapularis (the black-legged tick) affects TBD infections in our state. It includes information about Lyme disease and other TBDs present in Vermont including Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Borrelia miyamotoi, and Powassan Virus Disease.

About ‘Lone Star’ ticks:

- The VDH’s “Project Lone Star” is related to the presence of Lone Star ticks in Vermont. The VDH’s Tick Tracker has documented the presence of Lone Star ticks in several Vermont counties since 2014.

- Bradley Tompkins mentions (0:24) that the webinar focuses on “tickborne diseases that can be transmitted in Vermont”. Because data shows the Lone Star tick is present in Vermont, and the CDC refers to the Lone Star as “a very aggressive tick”, Vermont health care providers should be educated about diseases transmitted by this tick. These include Erlichiosis, red meat allergy, and Southern Tick Associated Rash Illness (STARI), which are not included in the webinar.

Why this is important: Vermont’s health care providers must know about the expanding presence of new tick species in Vermont, and have information about all species-specific diseases that have the potential to affect Vermonters both in state and during travel out of state.

COURSE OBJECTIVE #2: Symptoms

Dr. Jean Dejace (UVM Medical Center) presents a range of Lyme disease symptoms, explaining the differences between early and disseminated Lyme disease. Dr. Marie J. George (Southwestern Vermont Healthcare and Medical Center) discusses symptoms of Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, and Borrelia miyamotoi.

Dr. Dejace’s presentation included important information about atypical EM rashes in Lyme disease with link to excellent reference images.

About the Erythema migrans rash in Lyme disease:

- Dr. Dejace says (8:15) that “diagnosis of early localized Lyme disease is predominantly clinical based on the appearance of an erythema migrans rash”. This could be misunderstood as the rash being a requirement for clinical diagnosis.

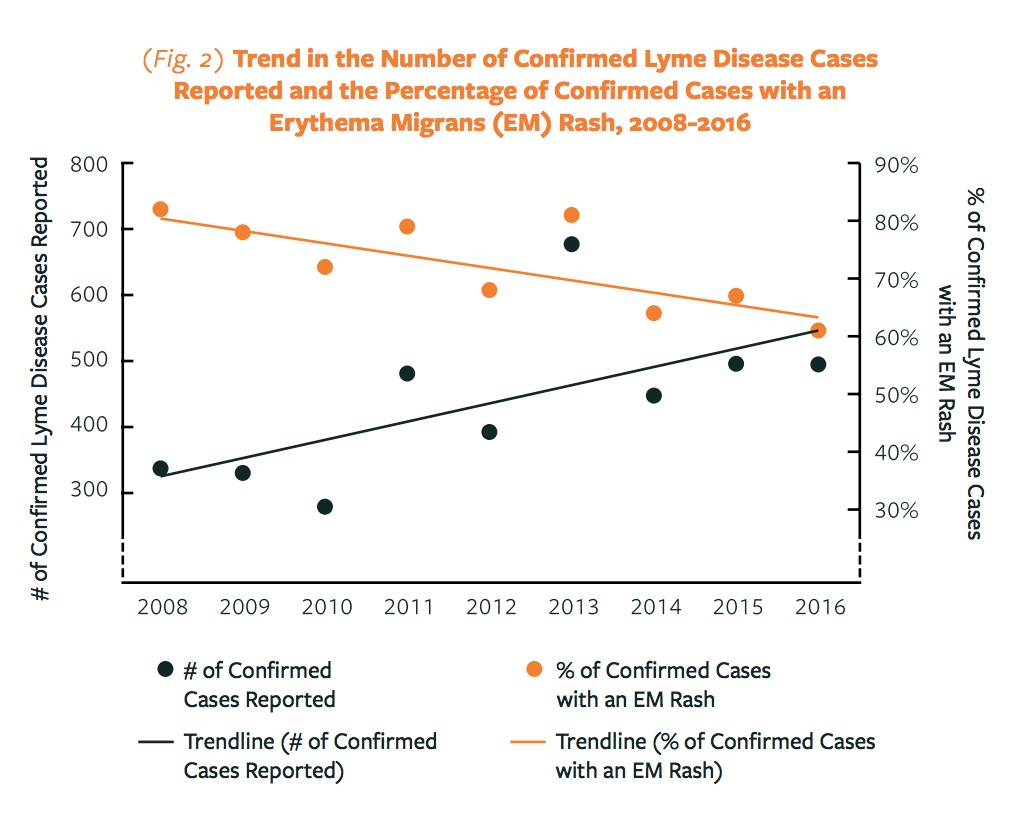

- Dr. Dejace continues, “the rash is present in about 75% of cases” however the VDH 2016 Tickborne Disease Annual Report showed EM rashes in confirmed Lyme disease cases in Vermont have been steadily decreasing, with the most recent published total being closer to 60%.

- Symptom data were not included the 2017 VDH report, but the 75% EM rate that Dr. Dejace refers to could be an average mentioned in that report, “During 2005–2017, more than 70% of Vermonters with confirmed cases of Lyme disease developed an erythema migrans (EM) rash.” However, this average over 12 years does not inform Vermont health care providers of the recent trend of decreasing incidence of EM rash in Vermonters with confirmed Lyme disease.

- The 2017 report states, “Other symptoms of Lyme disease, such as fever, chills, headache, fatigue and muscle and joint aches may occur with or without an EM rash.” In the webinar Dr. Dejace says (8:57) “In addition to erythema migrans, patients with early Lyme may develop systemic symptoms…” Again, this could result in a misunderstanding by some health care providers that an EM rash is required for a Lyme disease diagnosis.

- Dr. Dejace (9:37) does talk about “situations of diagnostic uncertainty.” Within this context, it would be important for health care providers to know more about data showing increasing diagnosis Lyme disease without an EM in Vermont. Vermont providers should also be informed that, according to the CDC, early or prophylactic antibiotic treatment may cause infected patients to test negative in later blood tests.

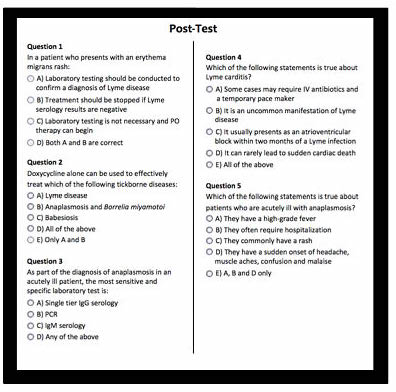

- The first question on the post test asks about treatment in the presence of an EM rash, but the more difficult (and relevent in Vermont) diagnosis in the absence of a rash is not addressed by this 5 question test.

Why this is important: It is agreed upon in the medical community that early diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease significantly reduces the chance of long-term complications and adverse impacts on a patient’s health. To ensure early diagnosis, Vermont health care providers must be knowledgeable about less traditional presentations of Lyme disease and the importance of clinical diagnosis in the absence of am EM rash, especially as VDH data shows the incidence of EM in Vermonters with confirmed Lyme disease is decreasing.

About symptoms and diagnosis in different stages of disseminated Lyme disease:

Dr. Dejace reviews symptoms and presentation of early disseminated Lyme disease (10:20) in three categories: skin, cardiac and neurologic. Late disseminated disease is also reviewed (12:40) with a sole focus on arthritic presentations.

- According to the CDC, in addition to the symptoms listed by Dr. Dejace, symptoms of disseminated Lyme disease may also include: “heart palpitations, episodes of dizziness or shortness of breath, inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, nerve pain, and shooting pains, numbness, or tingling in the hands or feet.”

- According the the VDH website, in addition to cranial neuropathy, radiculopathy and meningitis mentioned by Dr. Dejace (12:00), disseminated Lyme disease may present with “cognitive impairment, encephalopathy, and pain that comes and goes in muscles, bones and tendons.”

- Dr. Dejace notes that disseminated Lyme disease most commonly occurs “weeks to months after infection” (10:32). The VDH website says “Watch for symptoms of tickborne illness for three days to 30 days after a tick bite” and a VDH press release reads, “Symptoms may begin as soon as three days after a tick bite, but can appear as long as 30 days after”. The incongruity in Dr. Dejace’s statement in the webinar and messages from the VDH about the timing of symptoms may confuse patients.

- The emphasis on laboratory testing procedures for Lyme disease in the webinar does not make clear the CDC’s recommendation that Lyme disease be diagnosed “based on symptoms, physical findings (e.g., rash), and the possibility of exposure to infected ticks” along with the results of laboratory test results in patient assessment when indicated.

- Dr. Dejace does say issues with lab testing are “why clinical diagnosis is important” but the webinar offers no guidelines for clinical diagnosis.

Why this is important: Manifestations of disseminated Lyme disease can occur days, months or years after infection, and late disseminated Lyme disease can present with symptoms far different than the arthritic presentation Dr. Dejace describes in the webinar. Health care providers in Vermont should be made aware that additional symptoms mentioned above, or others including sudden onset anxiety or cognitive changes, may be related to disseminated Lyme disease or other tickborne diseases.

About cognitive or psychiatric presentations of Lyme disease:

Because Vermont is an endemic state with one of the highest Lyme disease rates in the USA, Vermont health care providers should know that disseminated Lyme disease may have a cognitive or psychiatric presentation. This requires providers to look past some symptoms to address underlying disease.

- For example, in the study of three cardiac deaths Dr. Dejace refers to (11:05) in the webinar, one patient had been diagnosed with anxiety just before his death, “The patient had complained of episodic shortness of breath and anxiety during the 7–10 days before death. No rash, arthralgia, or neurologic symptoms were noted. A physician consulted 1 day before death prescribed clonazepam for anxiety.”

Health care providers should be trained to consider a range of symptoms, medical and mental health histories, and patients’ likelihood of tick exposure in Vermont to rule out a tickborne disease diagnosis. Chronic, non-specific symptoms are covered briefly in the webinar (20:00) but only in the context of Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS), not as an aspect of clinical diagnosis.

COURSE OBJECTIVE #3: Testing

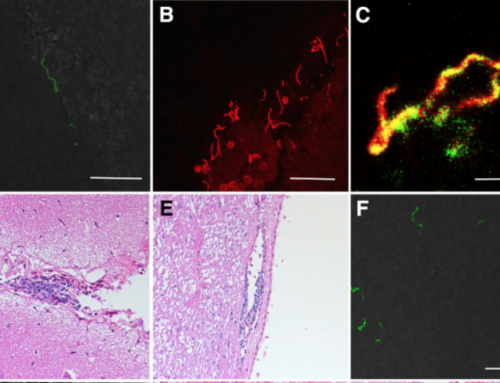

Dr. Dejace does a thorough review of two-tiered Lyme testing (4:38), and Dr. Marie J. George covers Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis and Borrelia miyamotoi. Beyond the VDH’s objective of ‘identifying tests used to diagnose tick-borne diseases’, different symptoms and presentations of TBDs in Vermont are covered. Dr. George discusses tests used to diagnose Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis and Borrelia miyamotoi. Regarding Lyme disease testing, Dr. Dejace notes (26:40) that “even the best Lyme testing is imperfect and should be interpreted in the context of the patient’s clinical presentation.”

Dr. Dejace discusses (5:50) some problems with Lyme disease testing in the webinar and reminds providers that is “why clinical diagnosis is important.”

About testing for Lyme disease:

- A paper (7:31) referenced by Dr. Dejace regarding his skepticism of commercial labs specializing in the diagnosis of Lyme disease (7:20) actually notes that “there was surprisingly little difference among the laboratories in percentage of positive results on most assays using CDC criteria”. The positive results by one lab Dr. Dejace refers to in his lecture are a result of that lab using unvalidated criteria that was different from the CDC’s.

- Dr. Dejace mentions (7:16) that identifying positive IGM bands on a Western Blot can be “particularly troublesome” and references a paper titled “High frequency of false positive IgM immunoblots for Borrelia burgdorferi in Clinical Practice.” However, the criteria used by researchers in this paper could be considered questionable. For example, researchers “assumed that positive IgM immunoblot test results occurring during the winter were most likely to be false positive” because subjects “were regarded as having essentially no tick exposure because they were tested during the winter months”.

Why this is important: While Dr. Dejace states that testing for Lyme disease is imperfect, the webinar references several studies to support using current methods instead of highlighting the need for Vermont’s health care providers to thoroughly understand the nuances of Lyme disease testing. This focus on testing protocols neglects to educate providers about how to incorporate clinical diagnosis as recommended by the CDC.

COURSE OBJECTIVE #4: Appropriate Antibiotic Treatment

Dr. George covers the treatment of Anaplasmosis (28:36), Babesiosis (38:38) and Borrelia miyamotoi (49:09). Dr. Dejace notes that the standard doxycycline treatment for Lyme disease also treats Anaplasmosis. This webinar gives Vermont providers information about tickborne diseases that are emerging in Vermont in addition to Lyme disease.

About prophylactic treatment for Lyme disease:

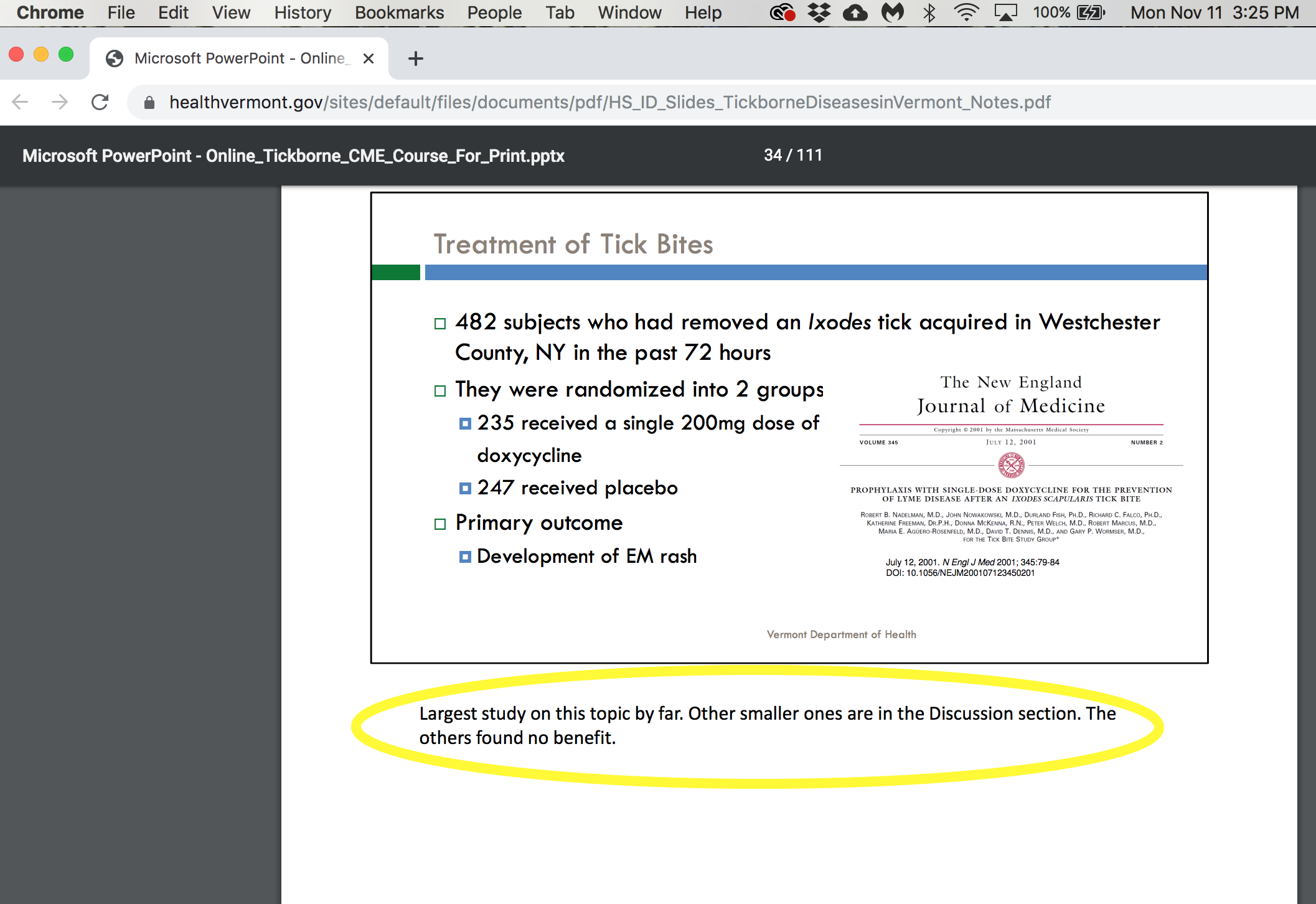

- Dr. Dejace reviews prophylactic treatment (14:00) for Lyme disease after a tick bite. He shares that this guideline is based on a single study where the primary outcome is the development of erythema migrans (EM) rash. Dr. Dejace notes that EM is “an imperfect measure” of whether a person is infected with Lyme disease.

- Dr. Dejace explains that other tick-borne diseases are not prevented by prophylactic doxycycline.

- Dr. Dejace’s own notes on this topic in the slideshow (#34) say, “Largest study on this topic by far. Other smaller ones are in the Discussion section. The others found no benefit.” Dr. Dejace does not make any mention of this lack of supporting evidence for prophylactic doxycycline in the webinar.

- Dr. Dejace does not discuss other important concerns regarding prophylactic treatment. For example, the duration of the study was only 6 weeks while the VDH and CDC note Lyme disease symptoms can present weeks, months, or years after infection.

- Also, it is not explained to providers on this webinar that, according to the CDC, prophylactic treatment with doxycycline may cause a person to test negative in blood tests even if they are infected with Lyme disease. This is important information for Vermont health care providers incorporating testing as part of a patient’s diagnosis.

Why this is important: Vermonters need to know that prophylactic treatment is not a guarantee they will not get Lyme disease. Providers who prescribe prophylactic treatment should know the limited research this recommendation is based on, educate patients about the symptoms of Lyme disease, and consider scheduling follow up appointments. Providers should also be aware of how prophylactic treatment may impact the results of future blood tests.

About patient outcomes:

Dr. Dejace shares several notable studies as part of “a substantial amount of evidence for good clinical outcomes” (16:17). An important consideration is how these studies do not reflect the diagnostic circumstances, timelines, treatment, or outcomes of many Vermonters being treated for Lyme disease.

- Both the Luger study (1995) and the (2003) Wormser study included only patients with physician-documented Erythema migrans. Therefore, most patients in these studies received early diagnosis and treatment. As discussed previously, a decreasing number of Vermont Lyme disease patients present with EM, and not all are diagnosed and treated early in their illness.

- The 2015 Wormser study measuring ‘Quality of Life’ was also limited to patients who had a confirmed Lyme EM. (The study authors acknowledged a “limitation of our study is that it was not directed at patients with extracutaneous manifestations of Lyme disease.”) In addition, 283 patients were recruited for the study but only 100 of these returned to fill out the ‘Quality of Life’ surveys throughout the duration of the study. The authors noted, “there was a significant difference in the number of baseline symptoms” between subjects who continued their participation in the study and those (with more symptoms) who did not. One could easily surmise that patients with more difficulties related to their illness would be less likely to continue their participation in the study, and therefore it is possible the 183 patients who did not return to complete the study would have been statistically significant in determining post-treatment ‘Quality of Life’. In addition to acknowledging this issue, the authors also noted that “Data from certain European studies have suggested that impairment in health-related quality of life may occur as a consequence of neurologic Lyme disease specifically.” (Neurologic disease being a different circumstance than the acute EM presentation of subjects in this study.)

- The Kowalski study (2001) included only patients with an EM or positive lab results. The study measured ‘treatment failure’, and defined ‘treatment failure’ as “a patient developing persistent erythema migrans despite antibiotic therapy”, or objective clinical and laboratory findings of progressive Lyme disease “not present on initial diagnosis.” In addition, “Patients who developed a second episode characterized by erythema migrans skin lesion(s) during a subsequent tick season were considered to have a reinfection not treatment failure.”

- These studies of patients with Lyme disease who were diagnosed and treated early still had up to 10% treatment failure rates. Again, early diagnosis and treatment results in a positive outcome in the vast majority of patients, but providers and patients should be informed about the possibility of treatment failure or extended recovery times that may require follow up visits.

- Vermont providers should know that Lyme disease patients will range from the early, acute illness (like the subjects in the studies presented by Dr. Dejace) to late, disseminated disease (not reflected in any of the studies presented in the webinar).

Why this is important: Dr. Dejace’s statement “We saw that the overwhelming majority of patients do well with standard treatment” (19:30) is based entirely on studies where most patients had documented EM, and were diagnosed and treated early in their illness. Therefore a more accurate statement by Dr. Dejace would be “the overwhelming majority of patients who are diagnosed and treated early do well with standard treatment” noting study results may not apply to Vermonters with later diagnosis or delayed treatment. These studies also relied on limited criteria for “treatment outcomes”. It is important for health care providers viewing this webinar to understand that the patients represented in the studies referenced by Dr.Dejace do not accurately reflect the diverse presentations of Lyme disease in Vermont, or treatment outcomes in Vermonters, including those with disseminated, neurological Lyme disease.

About Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS):

Dr. Dejace briefly discusses symptoms of PTLDS in a “minority of patients”, with a focus on not prescribing long term antibiotics as a treatment for PTLDS. He also notes that symptom resolution after Lyme disease treatment may take weeks to months (19:45).

- Dr. Dejace cites a study by Nowakowski as an example of a “subset of patients, perhaps 10%, who develop persistent subjective complaints (PTLDS).” But, like the studies mentioned previously, this study included only patients with EM who were “treated with antibiotics at the time of diagnosis.” Dr. Dejace notes (19:40) “none developed objective findings of late Lyme disease” but, like the earlier studies mentioned, the likely relevance of these patients’ early diagnosis and treatment to their outcomes is not mentioned in the webinar.

Why this is important: Studies of treatment outcomes can be skewed by only including patients with an EM rash who have received early diagnosis and treatment. These outcomes may not reflect the population of Vermonters with Lyme disease who do not present with a rash, and who therefore may have a delayed diagnosis, disseminated disease, or a delay in treatment.

Most patients with EM who get treated right away do have good outcomes, but the way this study is presented can misguide health care providers about outcomes including chances for developing PTLDS, in patients with delayed diagnosis, disseminated disease, or delayed or inadequate treatment.

About longer-term antibiotic treatment:

Dr. Dejace also discusses longer term antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease. While he presents a common view, his statement that “there is a strong consensus within the medical community regarding antibiotic therapy” (21:33) does not accurately represent the ongoing research, discussion, and debate by physicians regarding the treatment of Lyme and TBDs. Dr. Dejace covers three indications for IV therapy (19:19) and the possible need for extended antibiotic treatment of Lyme arthritis (18:35).

- Dr. Dejace lists 4 notable randomized human trials (22:05) “regarding prolonged antibiotics for Lyme” and stated “All reached similar conclusions.” However, a closer look reveals the studies have far too many variables to be accurately referred to as reaching similar conclusions.

- For example, one study by Wormser (2003) compared the difference between 10 and 20 days of doxycycline while the second study compared three months of IV oral antibiotics with placebos. A third study gave all patients IV ceftriaxone for two weeks, and then continued with three months of oral antibiotics or placebo. (This third study was done in Europe where Borrelia strains that cause Lyme disease are different, and according to the authors have “different clinical manifestations“ than those in the USA and Vermont.)

Why this is important: Presenting three extremely diverse research studies as definitively confirming a consensus about longer term antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease could be confusing to Vermont health care providers. It is important for Vermonters, and their providers, to understand that the treatment of Lyme disease is an emerging science, not one that has been settled by comprehensive and cohesive research.

About the misdiagnosis of Lyme disease:

- Dr. Dejace mentions a paper describing 3 cases where significant illness were misdiagnosed as Lyme disease (26:27). He does not mention that there is formal documentation of Lyme disease being misdiagnosed as Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis, cellulitis, multiple sclerosis, polymyalgia rheumatica, or as sports related injuries.

Why this is important: Vermonters and their health care providers should be provided with equitable information about the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. There are multiple physician documented cases of serious illnesses mistakenly diagnosed as Lyme disease, and also of Lyme disease misdiagnosed as another illness. In both scenarios comprehensive physician education would reduce incidence of misdiagnosis.

Conclusion

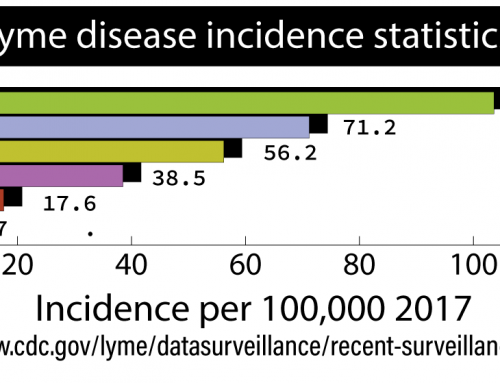

Tickborne diseases have a significant impact on Vermonters. In recent years, Vermont led the USA for incidence of Lyme disease. Other tickborne diseases are on the rise in Vermont, and a new tick species is likely in the process of establishing itself in our state.

It is commendable that the VDH has offered a webinar to help Vermont’s health care providers better diagnose and treat tickborne diseases, but this webinar reveals a need for additional, thorough and equitable information regarding the clinical diagnosis and effective treatment of Lyme disease.

Truly equitable information about Lyme and tickborne diseases would acknowledge that we don’t know what we don’t know. That being said, there is enough we do know about tick-borne disease to provide a basis for standard care. One could question if the 5 question long post test providing CE credits truly ensures Vermonts’ health care providers are adequately trained in the objectives of this webinar? This is of critical importance when Vermont’s children ages 5-14 are at highest risk for Lyme disease.

Vermonters and their health care providers need comprehensive education about Lyme and other TBDs. They should have accurate and up-to-date information about disease presentation in Vermont. Providers should be trained to understand potential problems with blood tests for Lyme disease, and be able to make a clinical diagnosis. Additional presentations of disseminated Lyme disease, like those listed on the VDH and CDC websites, should be included in the webinar. Providers should be trained to recognize psychiatric and cognitive manifestations of tickborne diseases, along with behavioral and other unique presentations of pediatric tickborne illness in Vermont’s children.

When we give Vermonters and their health care providers access to thorough and equitable information, we empower them to use their training, expertise, and experience to make informed and individualized health care decisions that benefit Vermonters affected by tickborne diseases, their families, their employers, and their communities.